Indian Football doesn’t need the next Sunil Chhetri; it needs the next Syed Abdul Rahim

Indian football stares into dire straits with domestic football stalled indefinitely.

Sunil Chhetri was never the product of a golden generation or a perfectly aligned system, but he survived despite Indian football’s structures, not because of them. Framing the future of the national team around finding another outlier takes the focus away from the absence of systems capable of identifying, developing, and sustaining talent.

History has already shown that Indian football’s most successful eras were not built only on gifted individuals, but coaches who built systems around the players’ strengths and weaknesses to squeeze every drop of high performance from them.

Syed Abdul Rahim’s pioneers of the 50s and 60s, Sukhwinder Singh’s nearly-men of the 2000s and the two AFC Asian Cup campaigns of 2011 and 2019 under Bob Houghton and Stephen Constantine cometo mind when the Indian Men’s National Team was able to hold its own against continentalbigwigs.

Today, the influx of foreign coaches has impacted the Indian coaching ecosystem positively and negatively. There is no doubt that many active Indian coaches have benefited from working with high-profile and highly experienced European coaches who have contributed to the professionalisation of club football by incorporating modern methodology.

But this has led to a combination of an overreliance on imported knowledge and a lack of trust in givingcharge to Indian coaches, and the creation of a comfort zone for Indian coaches to play second fiddle with little accountability.

This raises a more fundamental question. If India wants better footballers, where are its elite coaches and scouts coming from? And what does the current coaching education system prioritise: quality or quantity? An analysis of AIFF’s coaching database suggests a system skewed heavily towards mass certification at the entry level, with little emphasis on progression, specialisation, or contextual relevance.

Quantity over quality

As of December 13, the AIFF’s coaching database lists 16,317 licenced football coaches across states and Union Territories who have attained a minimum ‘D’ certificate. Although the AIFF introduced an ‘E’ certificate recently, it does not add significant value or knowledgeto that received in a ‘D’ certificate course.

This number also excludes the foreign coaches who completed their Pro Licence course in India but no longer work in the ecosystem. On the surface, this looks like evidence of a sport expanding its base, but when licence distribution is examined more closely, the picture changes dramatically.

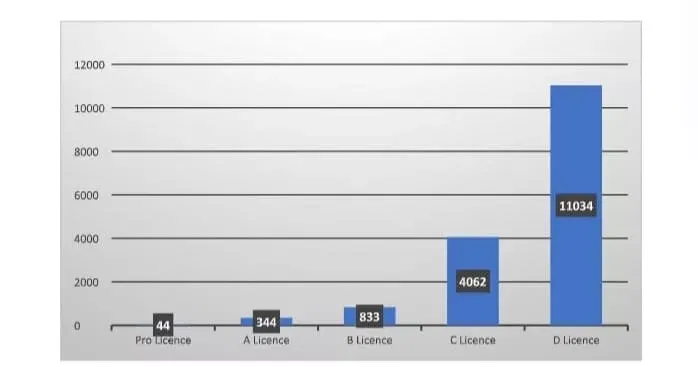

Across the country, more than two-thirds of all licensed coaches hold only the AIFF ‘D’ Licence, the entry-level qualification, while a further large share, about 25%, are at AFC ‘C’ level. By contrast, coaches with AFC ‘B’, AFC ‘A’, or AFC Pro licences make up only a small fraction of the system.

The number of Pro-licence holders, those qualified to coach at the highest professional level, is currently 44 or 0.27% of the total licensed coaches in India. his illustrates a wide coaching bas,e but the pyramid narrows sharply long before coachesreach senior levels.

Every coach must start somewhere and this is where the system has democratised entry byfocusing heavily on participation to get prospective coaches licensed quickly. Courses arefrequent and entry barriers are relatively low even though a fee above Rs. 10,000 for a ‘D’licence still feels steep.

However, there are no studies available to track the progress made by licensed coaches tocheck how many ‘D’ licensed coaches attempt a ‘C’ licence and so on, how long thisprogression typically takes, or how many drop out altogether.

“We currently do not have any progress tracking mechanism or mentorship programmes inplace for our licensed coaches,” said Vivek Nagul, AIFF Head of Coach Education. “For us,any coach getting an opportunity to put into practice what they have learned during thecourse can be considered a success.”

More Coaches ≠ Better Coaches

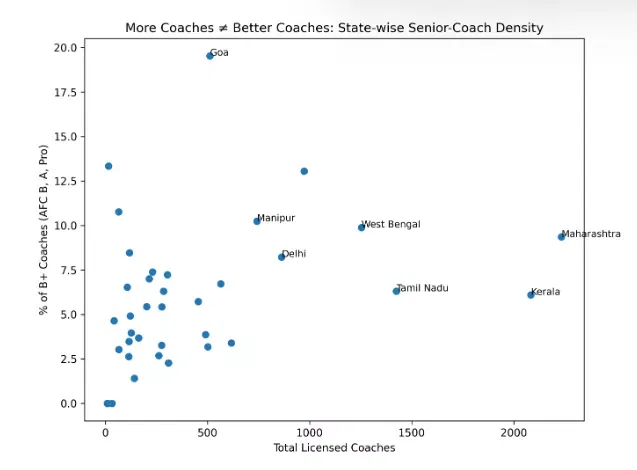

The state-wise breakdown of coaching data exposes another problem. States such asMaharashtra (2,233 coaches), Kerala (2,083), Tamil Nadu (1,425), and West Bengal (1,254)dominate Indian football in sheer coaching volume.

Together, they account for a significant proportion of all licensed coaches in the country. Yet when we examine the percentage of senior coaches (AFC ‘B’ and above), these states do not stand out in the same way.

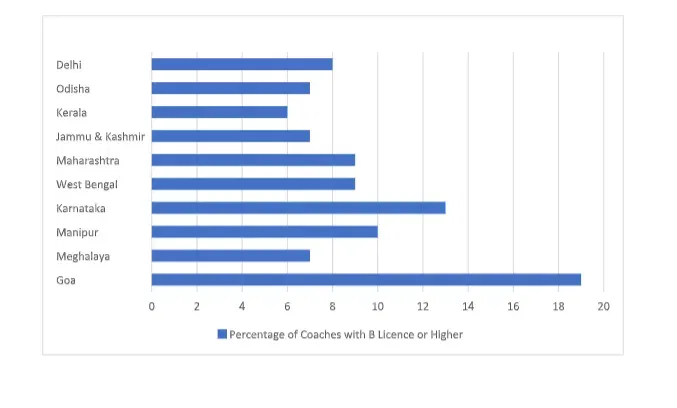

This scatter plot dismantles the assumption that scale automatically leads to quality. Keralaand Maharashtra sit far to the right for producing massive numbers of licensed coaches butrelatively low on how many highly qualified ones they have.

Delhi and Tamil Nadu show similar patterns. Goa, by contrast, stands out immediately. With just over 500 licensed coaches, it has the highest proportion of senior coaches in the country. Goa’s position on the graph reflects fewer coaches entering the system, but those who do are far more likely to progress.

Highly qualified coaches shape training environments, talent identification, player roles and transitions, and long-term development plans. A system that produces many entry-level coaches but few senior ones will inevitably struggle to identify and develop elite players.

The North-East: Culture is doing the heavy lifting

If coaching licences explained talent output, the North-East would dominate senior licencesbut the reality is different. Nowhere is the disconnect between output and structure more prominent than in the North-East. States such as Manipur, Mizoram, and Meghalaya continue to produce a disproportionate number of professional footballers.

Research by Richard Hood shows that professional playing minutes and debuts in Indian football are heavily concentrated in this region.

Yet when we look at coaching data, these states do not dominate in senior licences. Manipur performs better than the national average with 76 coaches with ‘B’ licences or higher, but it is not structurally ahead of larger states.

“Employment dynamics play a big part in producing big numbers of coaches,” said Hood.

“Bigger, urban regions have created more opportunities for various levels of coaches to find employment in school teams, academies, clubs, and corporates. In the Northeast, a ‘C’ or a ‘D’ Licence is sufficient for the ecosystem where not many coaches are comfortable in English or can afford to pay for a ‘B’ or ‘A’ licence.”

It is a strong foundation to build on but does not seem sustainable. Without stronger coaching pathways, even the most fertile football regions eventually plateau. One solution that springs to mind is to fast-track coaches from the most football-fertile region in the country into higher coach education programmes. Hood, however, disagreed.

“Informal football environments like community leagues and school tournaments draw froma large base of youth teams giving more access and promoting the local football culture in these regions which will in turn further increase the number of players being produced as opposed to plateauing,” said Hood.

“Fast-tracking will not help because whatever licence coaches hold, their development will be hampered if they do not get competitive matches to test themselves much like players. “

From coaching to scouting: The missing link

There are frequent complaints in Indian football that talent is “falling through the gaps.” The usual response is to call for better scouting networks. But in India, most scouts are usually coaches in academies at various levels.

If the majority of them are operating at entry-level qualifications like ‘D’ or ‘C’ licence, their scouting inevitably prioritises player traits that are easiest to identify, like physicality, size, and short-term dominance.

As coaches progress through their education, advanced levels equip them with better tactical understanding, positional intelligence, understanding decision-making under pressure, and long-term developmental projection. These would help identify a better player rather than a bigger, stronger or faster player.

“It is one of the major reasons talent slips through in India but not because ‘D’ or ‘C’ licence coaches are bad, but because scouting and coaching are two different skill sets,” said Stephen Charles, Head Scout at Reliance Foundation Young Champs. “Coaching licenses focus on coaching and not scouting. There is always an edge for a person to scout or identify talent if he or she has played the game at a good level, or has enough coaching experience at a good level.”

However, there is no guarantee that a higher licence can develop a better eye for spottingtalent.

In July 2024, then India U17 coach Ishfaq Ahmed, a Pro Licence holder and head coach of Real Kashmir FC, reportedly told scouts to look for “tall, strong” boys after watching Lamine Yamal and some Japanese school teams during his trip there.

“While everyone wants quick results and readymade players, coaches often select players who are early developers which include bigger, faster, stronger players who have matured early,” observed Charles. “Late developers, intelligent movers, and technically gifted but physically less imposing players are filtered out too early making it one of the biggest leak points in the Indian talent pathway.”

The AIFF used to outsource their scouting curriculum to the International Professional Scouting Organisation (IPSO) which conducted workshops, online and in-person, over three levels but that partnership has now concluded.

“We have planned four Regional Introductory courses for the upcoming year for which we have also decided to develop and upgrade our tutors,” said Nagul.

This could be classed as another example of Indian football borrowing frameworks from Europe or the United States like licensing structures, competition formats, and age-group models without adapting them to local realities. The result is a system that looks modern on paper but struggles in practice.

“While there is no shortage of talent in India, it does lack a scouting framework that understands its people, its regions, and its timelines,” said Charles. “The AIFF should aim to separate scouting from coaching and not keep treating it as an add-on to coach education. When scouting is done through a coaching lens alone, talent is filtered by convenience, not potential, because some coaches subconsciously prefer players who fit their system or respond quickly to instruction. Scouting requires letting go of systems, seeing beyond your own philosophy, and accepting uncertainty.”

If Indian football is indeed heading towards some form of a reset, it makes sense to introduce reforms in the coaching and scouting curriculum as well. Asian football is moving forward with an alarming pace, and India are yet to move into second gear.

It is high time the decision makers adopt a data-oriented approach with actionable solutions to existing problems instead of praying for miracles. Indian football is not failing to produce talent but at the moment, it is failing to recognise, nurture, and retain it.

For more updates, follow Khel Now on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Youtube; download the Khel Now Android App or IOS App and join our community on Whatsapp & Telegram.