Decoding the Downfall of Maharashtra Men’s Football Part 1: Success Without Succession (2000-2010)

The warning signs behind Maharashtra football’s decline.

As 2025 draws to a close, Maharashtra men’s football has been shaken to its core by two developments in the space of three days, which could have dire consequences for the ecosystem in the years to come.One of these developments, understandably, garnered much more attention, even making Fabrizio Romano post on his social media channels. That was City Football Group’s exit from Mumbai City FC and subsequent transfer of their majority stake to Bollywood actor Ranbir Kapoor and businessman Bimal Parekh, as revealed exclusively by Khel Now.

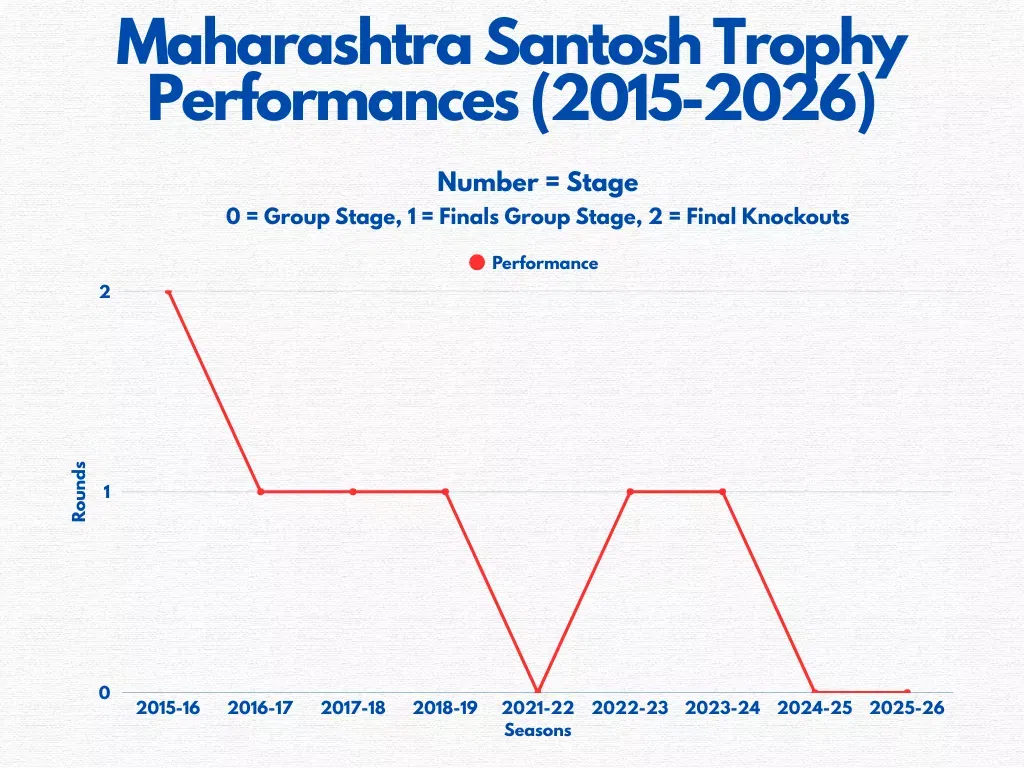

The other flew completely under the radar, as it has tended to, and that was Maharashtra’s exit from the Group Stage of the 2025-26 Santosh Trophy being held at various venues across the country. This was their third exit from the first round in the last five years, with the governing body, Western India Football Association (WIFA,), neither taking accountability nor the local sports media or stakeholders demanding it.

It proves that football does not wait for anyone to rest on their laurels, with the likes of Gujarat and Rajasthan now outperforming Maharashtra in national-level men’s competitions. S,o where has it gone downhill for a state which boasted iconic clubs and tournaments?

This three-part series aims to get to the bottom of that notion by talking to former players, officials, and other stakeholders who have been involved in Maharashtra men’s football over the last three decades.

Mahindra United and Air India: The Twin Pillars of Maharashtra Football

Two institutions of varying structures that kept Maharashtra football’s flag flying high in the 2000s were Mahindra United and Air India FC, the former representing a new wave of corporate professionalism and elite ambition, while the latter embodying public sector security and continuity.

Rebranded in 2000 from Mahindra & Mahindra Allied Sports Club, Mahindra United were among the first Indian clubs to function with a recognisably professional framework with infrastructure and modern methodology. Former Indian international and current Jamshedpur FC head coach Steven Dias spent seven seasons with the Jeepmen, and he told Scroll about how the club had their own training ground, gym, swimming pool and monitored diets.

Their dominance of the Mumbai Football League, winning the title eight times in a decade, established them as the state’s undisputed flagship club. But it was their 2005-06 National Football League title, the first by a Mumbai-based team, that elevated Maharashtra into the national elite. Completing a historic league and Federation Cup double, Mahindra United briefly disrupted the Kolkata-Goa axis that had controlled Indian football for decades.

More importantly, Mahindra United created an environment where Maharashtra players could aspire without leaving home, with the likes of Dias and Khalid Jamil central to title-winning sides and national team setups. For players coming through Mumbai’s local leagues, Mahindra represented a club that expected international standards from Indian footballers and provided the infrastructure to meet them.

So, when Mahindra United decided to withdraw from senior football in 2010, citing a strategic shift toward grassroots development, Maharashtra lost its most powerful club overnight. The system did not collapse immediately but it never recovered.

While their more illustrious neighbours were grabbing headlines, Air India FC performed the less glamorous but equally vital role of keeping Maharashtra football alive. Based in Mumbai and backed by a public-sector institution, Air India was a constant presence in the National Football League and early I-League during the 2000s. They were rarely title contenders, but they were consistently competitive and, more importantly, consistently operational. Players in Air India were employees first and footballers second, which allowed many to remain in the game longer than they otherwise could have.

“Having the security of a public sector job helped players focus fully on their football, but more than that, it was the platform that clubs like Air India FC gave which helped us launch our careers at the national level,” said Abhishek Ambekar, who won the I-League with Minerva Punjab in 2018 before going to play for all three Kolkata giants. “Although we did not get the luxuries like some professional clubs offered at the time, Air India FC ensured that basic standards did not drop when it came to travel, stay, nutrition and training.”

This institutional model served Maharashtra particularly well in the 2000s because, unlike states that depended on a single dominant club, Maharashtra had a middle tier where players who may not have been national team regulars sustained competitive depth across leagues, Santosh Trophy squads, and local competitions.

Air India’s continued participation in the Mumbai Football League also ensured that local football remained competitive and relevant, feeding talent upward even as national structures fluctuated. But like Mahindra United, Air India’s model was not future-proof. As public-sector support for football diminished in the late 2000s, institutional teams across India began to withdraw, and Maharashtra lost yet another stabilising force.

Pune FC: A Serious Club in an Unserious Ecosystem

If Mahindra United represented elite professionalism and Air India represented institutional stability, Pune FC represented the unrealised possibility of decentralisation in Maharashtra football. Founded in 2007 by the Ashok Piramal Group, Pune FC made their way up through the district leagues to qualify for the I-League in 2009 with a mix of local, regional, national, and overseas talent. The Red Lizards had five top-5 finishes in their six seasons in Indian football’s top flight before shutting down operations in 2015.

With investment at all levels of the club, Pune FC achieved many firsts, like signing a player from the top 10 European leagues (Edmar Figueira from CD Feirense), playing a friendly against a Premier League club (Blackburn Rovers) and getting a transfer fee for selling a player to a fellow I-League side (Lester Fernandez to Prayag United). The club also launched the careers of many Indian internationals like Amrinder Singh, Semboi Haokip, and Salam Ranjan Singh while giving local players like Paresh Shivalkar and Prakash Thorat first-team opportunities.

Pune FC also cast a wider net for talent identification in Maharashtra, and the story of Nikhil Kadam stands out in this regard. The left-footed attacking midfielder followed the now well-trodden path from his native Kolhapur to the Krida Prabodhini academy in the Balewadi Sports Complex and impressed the club on trial.

He became the first academy graduate to earn a senior professional contract and made 28 appearances for the club. Kadam went on to have a respectable career in Indian football, playing for the likes of Mohun Bagan, NorthEast United and Mohammedan SC before injuries started taking a toll.

On the ground, the club became an aspirational pathway for the city’s budding football players when everyone wanted to play for Pune FC. Shanmugam Venkatesh, Douhou Pierre and Arata Izumi became local heroes, with the latter becoming the first overseas player to take up Indian citizenship and play for the Blue Tigers.

Maharashtra’s second city was building its own football identity, but it was predictably let down by an ecosystem which was having its head turned by the new kid on the block – the Indian Super League.

The Rovers Cup: How Maharashtra Let Its Greatest Tournament Die

How does a tournament that has run for over 100 years, punctuated only by World War I and India’s independence, become defunct merely a decade after celebrating its centenary?

Long before the ISL arrived with broadcast deals and branding exercises, the Rovers Cup was Mumbai’s footballing heartbeat. Founded in 1891, the Rovers Cup was India’s third oldest football tournament after the Durand Cup and Trades Cup, and, for decades, one of its most prestigious. It regularly featured top Indian clubs from Kolkata, Goa and the Services, while also bringing over foreign teams from Central Asia, Africa and the Middle East. For local players, the Rovers Cup was not nostalgia or prestige but an opportunity where a strong performance could mean national recognition, trials at bigger clubs, or selection into state or Services teams assuring job security.

By the early 2000s, however, the tournament’s decline was already underway. The official website of WIFA has a page on the Rovers Cup where it blames the tournament’s decline on the inception of the NFL and the eventual winding up on “huge costs and sponsorship deals issues”. By this, one could assume a lack of coordination with the AIFF over scheduling clashes with league fixtures, a lack of promotion leading to sparse attendances, or stagnation of prize money due to a lack of credible sponsors.

The death of the Rovers Cup took away not just a legacy tournament but a scouting platform, cultural anchor, and a rare bridge between grassroots and elite football. Mumbai, and by extension Maharashtra, lost its most visible footballing identity before Mahindra United and Air India replaced it.

By the end of the 2000s, Maharashtra football had been hollowed out by the exit of Mahindra United, the discontinuation of the Rovers Cup and Air India stepping back from national participation. Pune FC stood alone outside Mumbai, fighting structural battles it was never meant to win.

The state still produced footballers and filled Santosh Trophy squads but the institutions that once converted participation into progress no longer existed. What replaced them was fragmented ambition, administrative inertia, and a growing dependence on Mumbai as the sole centre of gravity.

The 2010s promised revival. Instead, they exposed how fragile Maharashtra football had already become. Part II examines the decade where Maharashtra football had visibility, money, and national relevance yet somehow slipped further behind.

For more updates, follow Khel Now on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Youtube; download the Khel Now Android App or IOS App and join our community on Whatsapp & Telegram.